Women in STEM - Trota of Salerno

Trota and Trotula

When I first googled “Trota,” this is what came up:

“‘Trota’ is the Italian word for trout, a freshwater fish. The term is also used to refer to the fish as a food.”

I understand that this is technically correct, but there wasn’t even an option for Trota being an influential woman of her time. I was offered Italian for trout or a transport company by this name.

To find her, I had to search specifically for Trota of Salerno. By all means, tell me it’s Italian for fish and there is a transport company with this name, but it was disappointing that Trota of Salerno didn’t even feature in the top search results. Yet, in the 12th century, this woman was one of the most respected medical practitioners in Europe.

This has now been changed, and Trota appears within the search outline and in the top search results when you search just 'Trota'.

Trota and what she means today

When people name medieval healers, it’s often men who come to mind, women were seen as “midwives”. Yet in the 12th century, in the port town of Salerno, a woman named Trota was writing prominent and practical medical advice that would travel across Europe. Her work is among the clearest and most influential pieces of evidence we have that women practised and wrote about medicine in the Middle Ages. Their work went beyond midwifery, general therapeutics, cosmetics, and issues of fertility and hygiene.

Trota’s surviving work shows a clinician who combined pragmatic remedies with frank, sometimes surprising, observations. For example, she acknowledged that both partners contribute to infertility, an eye-opening statement in its time and it challenged the long-standing Galenic view that women were primarily to blame. This secured Trota as an important voice in women’s medicine and the broader history of medical thought.

⸻

Salerno and the medical culture that produced Trota

Salerno, southern Italy, was home to the Schola Medica Salernitana, cited as Europe’s first medical “school.” It was a meeting point of Greco-Roman, Arabic, Jewish and Latin traditions. Unusually inclusive: evidence suggests that women (the mulieres Salernitanae) could practise as nurses, midwives and healers alongside men.

Trota emerged in this environment. While records are fragmentary, the texts associated with her show both practical authority and a keen observational eye. Remedies were often herbal (sage, rue, pennyroyal), but she also described diagnostic methods based on symptoms, touch, and patient narratives. In a period when medicine was deeply shaped by Galenic “humoral” theory (which framed illness as an imbalance in the four body fluids), Trota’s pragmatic focus on what worked set her apart. Her approach was based on observation and results over abstract medical doctrine.

⸻

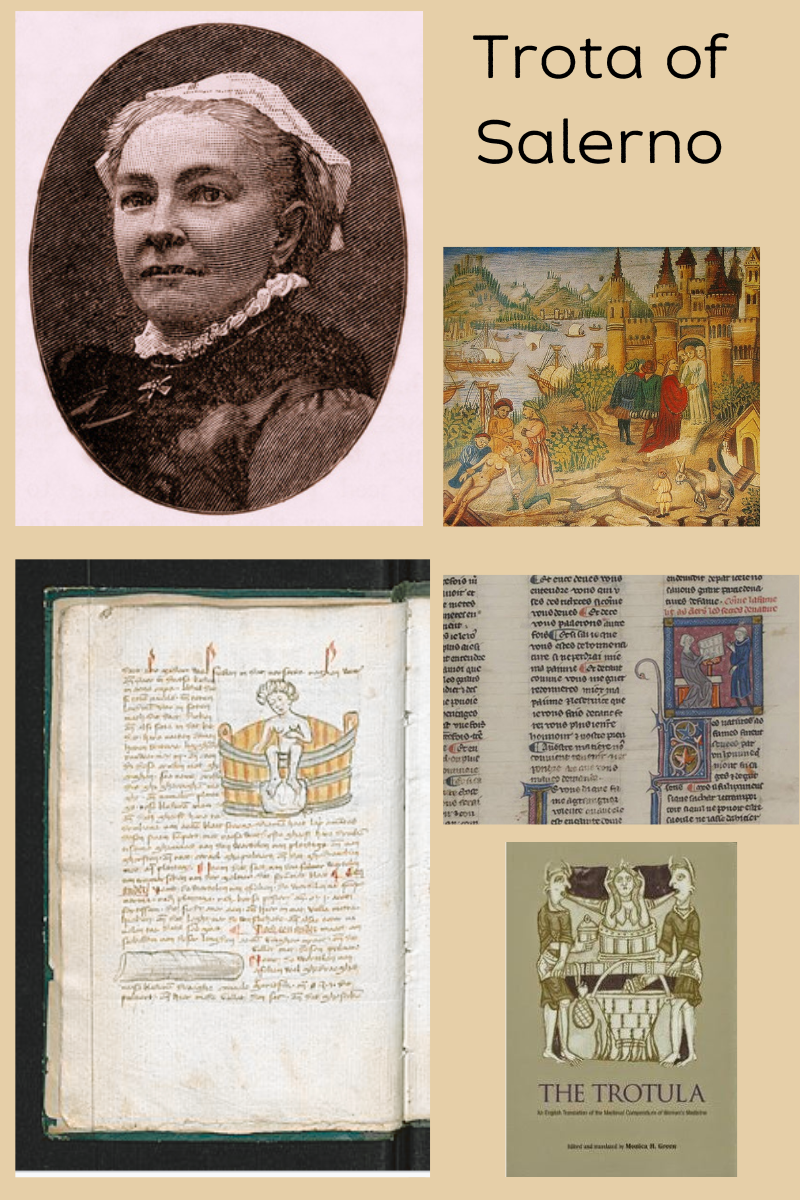

Trota and “Trotula”? Clearing the confusion

For centuries, readers encountered the name “Trotula” as the supposed author of a famous compendium on women’s medicine. New research, however, shows that “Trotula” was never a person but Trota’s texts. The name comes from a misunderstanding: by the late Middle Ages, three separate Salernitan texts on women’s health had been bound together and transmitted as a single work.

These were:

1. De passionibus mulierum ante in et post partum (on gynaecological disorders).

2. De ornatu mulierum (on cosmetics).

3. De curis mulierum (on treatments for women) - the text most directly linked to Trota.

The whole collection came to be called Trotula. Over time, scribes and readers assumed “Trotula” was the author’s name. In reality, with a lack of records, only some of this material can be securely attributed to Trota herself.

It was historian John F. Benton (1985) who rediscovered a manuscript of Practica secundum Trotam in Madrid, providing direct evidence of a historical woman named Trota. Building on this, Monica H. Green has carefully reconstructed which passages of De curis mulierum are likely Trota’s, and which are later additions or composites. While scholarly debate continues, the consensus today is that Trota was indeed a real figure, and at least part of the Trotula tradition preserves her voice.

⸻

What made Trota distinctive?

Trota’s remedies stand out for their blend of empirical observation and inherited theory. Where Galenic medicine emphasised balancing the four humors, and Arabic physicians like Avicenna systematised theory into encyclopaedias, Trota’s approach was more hands-on and patient-centred.

Examples include:

• Infertility: Rather than placing blame on women, she proposed tests for both sexes. Such as examining whether semen was retained or expelled after intercourse.

• Menstrual regulation: She recommended herbs such as rue and pennyroyal, alongside dietary adjustments, to restore delayed menstruation.

• Postpartum care: She offered guidance on easing uterine pain and swelling after childbirth, including poultices and baths.

• Cosmetic and dermatological advice: From removing blemishes to hair care, reflecting the overlap between medicine and beauty.

One striking passage paraphrased from De curis mulierum suggests: “When the womb is dry, conception cannot occur, but when it is too moist, the seed slips away.” This vivid image shows how Trota described bodily processes in practical, experiential terms and more than abstract humoral theory.

⸻

Beyond women’s medicine

While Trota is best known for her work on women’s health, evidence suggests her scope was broader. The Practica secundum Trotam includes remedies for fevers, wounds and digestive complaints, showing her as a general practitioner. This is significant: it counters the stereotype that medieval women were confined only to midwifery. Trota’s presence in multiple manuscript traditions indicates she was recognised as a medical authority beyond “women’s matters.”

⸻

Reception and legacy

Trota’s influence spread widely. The Trotula ensemble circulated across Europe, copied into Latin, translated into vernaculars like Middle English and Old French, and read by both laypeople and university-trained physicians. At Montpellier and Paris, the compendium was taught as part of medical curricula well into the 15th century.

Yet the process of transmission also distorted her authorship. As “Trotula,” she became a semi-legendary figure: sometimes mocked as an “old wife,” sometimes praised as a woman healer, but rarely acknowledged as the real Trota of Salerno. Only with the work of 20th- and 21st-century historians has her historical presence been recovered.

⸻

Trota’s works Now

Trota’s significance is twofold. First, she stands as rare documented proof that women were practising and publishing medicine in medieval Europe. Second, her work challenges stereotypes about the Middle Ages as uniformly hostile to women in science. In Salerno, at least, women like Trota could achieve visibility, even if in later centuries their contributions were obscured.

Trota’s story reminds us how fragile the record of women’s intellectual labour can be. A woman’s voice was almost erased, folded into a fictional “Trotula.” Recovering her words restores not only one medieval healer, but a lineage of women’s participation in science and medicine.

⸻

Further Reading, Book links and Information